This is a guest post by Harry Webne-Behrman. This article is adapted from his recent book, What Matters in This Moment: Leading Groups Through Uncertain Times.

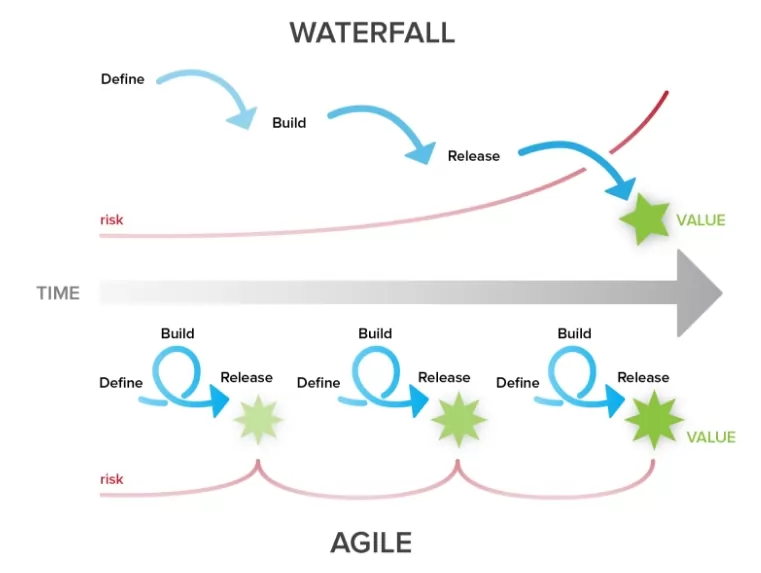

“Agile” and “Waterfall” offer us very different approaches to project management. These processes can each guide us, depending upon our goals, knowledge, and values surrounding stakeholder engagement. For those of you already familiar with either process as practiced in IT, I offer this with an eye towards broadening that understanding, applying these approaches to new types of situations. For others, I ask you to consider the values that each approach brings to the table, whether you are formally using them or not.

Waterfall process tries to understand the desired customer endpoint or result: “Where do you want to go?” is the guiding question, and we develop solutions based upon our understanding of the answer. We might begin with a requirements gathering process in order to understand resources and parameters, and stay within the scope of the Project Charter that emerges from that process. If we can understand this set of desired outcomes, we can plan backwards from that endpoint to determine a series of steps in product or service design.

Agile design, on the other hand, begins without a clear endpoint, assuming that any presumptions about results may bias or limit our opportunities and options. “What do our customers care about?” becomes the salient question, and discovering the likely answers determines the responses that will be developed. We try to listen empathically to our customers, understand the range of partners and other stakeholders who may have influence within the system, and begin to develop strategies that account for diverse actors and perspectives that may continue to unfold. Agile invites us to think divergently, keep experimenting and iterating, then prototype some promising options before settling on what emerges as best responses and outcomes.

Core Elements of Waterfall

Waterfall was first developed in the manufacturing and construction industries in the 1970’s, but it gained broader traction in the emerging IT field of the late 20th century. It is a highly structured process, generally represented by these distinct stages:

Step 1 – Define: Gather requirements from the clients and end users, understanding their vision for the project and desired results.

Step 2 – Design: Build a system that responds to these requirements. This includes systems architecture, as well as specific hardware and software systems.

Step 3 – Implement: Develop and build prototypes (called “units”) that respond to these requirements and meet specifications of the project.

Step 4 – System Testing: TEST! TEST! TEST! Rigorous assessments measure the effectiveness of the early releases in terms of the system requirements.

Step 5 – Release: Deploy the system, and assess results in order to best understand ROI, strengths and weaknesses of each product or service.

Step 6 – Maintenance and Value Assessment: Once released, there is a commitment to maintain the implemented system, make necessary adjustments, and continuously assess progress. Determine which additional investments are needed in light of this system now being in place.

A Waterfall variant, ADDIE, is commonly used in course development and professional training. It similarly looks first at the desired endpoint and then works backward to achieve that preferred destination.

Core Elements of Agile

Agile is a more recently developed process, first adopted as a term in the early 2000’s by software developers gathered in Snowbird, UT to represent a basket of flexible planning methodologies. It is characterized by constant iteration and collaboration, where the group’s learning is applied to continuous improvement of ideas. The original developers articulated an Agile Manifesto that reflects four core values:

- Individuals and interactions over processes and tools;

- Working software over comprehensive documentation;

- Customer collaboration over contract negotiation; and

- Responding to change over following a plan.

Rather than awaiting well-developed solutions before re-engaging customers, Agile continuously consults with them and redefines direction as a result. Agile methodologies are expressed through the Agile Life Cycle:

Envision: The project is conceptualized, stakeholders are identified, and initial scope is defined.

Speculate: Offer an initial sense of the project’s high-level milestones, as well as likely tasks required in order to achieve them.

Explore: Project teams creatively explore options regarding how best to achieve a specific milestone. They focus on one aspect at a time until they are satisfied they have a good working response or solution. The team stays within its scope and parameters, to be sure, but they also engage in creative thinking about the problem they are addressing.

Adapt: Through continuous feedback from customers and other stakeholders, initial solutions are adapted and revised, still staying within realistic parameters. There is a commitment to aligning elements with one another to form a coherent, integrated whole.

Close: The project team delivers its final product, checking to be sure it has satisfied requirements as they were more fully understood through the process. There is also a commitment to review the process and errors that may have been made, so there is learning that may be applied to future efforts.

Integrating Agile Approaches into Waterfall Cultures

As a consultant, one of the common issues I hear from clients is the challenge of helping their organizations make the transition from Waterfall practices and structures to Agile approaches to project management. We need to normalize this challenge as one of cultural transition, and respect that it will take a while to make it work. How we frame the issues and concerns becomes critical to this process:

This is much more than a “Technical” Issue: While we acknowledge that the technical elements of an Agile approach challenge us to continuously test, reflect, prototype further, etc., the key points of resistance come from the social and political dimensions of the problem. Invite conversations around the range of concerns present (see my book, What Matters in This Moment, regarding transition, conflict, and engagement for further elaboration), and create strategies that address those transition needs.

Explore how organization structure facilitates or inhibits this transition: In traditional command and control hierarchies, Waterfall is integrated into the cultural norms regarding how policies are created, who’s included, and how decisions are made. An Agile approach requires greater decentralization and cross-pollinating approaches to innovation, which in turn means that those with power need to intentionally examine how that power may be redistributed to facilitate the change.

Create “brown bag” workshops or similar educational opportunities: Never assume that people already know what this transition means in practice. These can become “teachable moments” for the management team, for departments that have traditional hierarchies and protocols, and for clients to more fully understand the Agile principles and core approaches.

Document pilot projects, then SHARE those stories: Many of us gain our greatest satisfaction from simply doing the work. Whether it means developing creative solutions to problems or navigating complex sticking points in implementation, there is a story to tell. While we recognize the value of documenting our processes, this task is often deferred or overlooked. But this is critical to the longer term vision of facilitating cultural change: Careful documentation, including both successes and failures, clear findings and unknown outcomes, needs to happen. Then get it translated into a new narrative, one that informs stakeholders and invites conversations around how these initial experiences may be replicated in other projects. The more the conversation can shift in this direction, the better the likelihood that the values and language of the new Agile approach will take root and be accepted into the norms of the organization.

Agile and Waterfall approaches each have their advantages and purpose. But if we are truly committed to creating nimble, innovative organizations that can respond effectively to emergent challenges and increased uncertainty, Agile processes offer an important path forward for corporate cultures that resist change or rely too heavily on the supposed certainties of planning processes. This article has offered a few places to start I hope you find useful.

About the Author

Harry Webne-Behrman has served as a facilitator, consultant, educator, and mediator for over 40 years. Along with his wife, Lisa Webne-Behrman, he served as Senior Partner of Collaborative Initiative, Inc., a private consulting and mediation firm based in Madison, Wisconsin from 1991-2017, before moving to Ottawa, Canada, where he currently works and teaches. Harry has worked with hundreds of businesses, educational institutions, community groups and public agencies, helping address entrenched organizational and social issues. By consulting with leaders, facilitating large-scale deliberation and engagement processes, mediating interpersonal disputes, and offering educational programs that develop skills needed to address such challenges, Harry has earned a reputation as a valued resource and guide.